This was written in the days of June 19th and 20th. It's mostly unchanged from that time and any addition was made after its end.

Rough and Rowdy Days

The immeasurably long quarantine started, if I'm not mistaken, in early March. In a city of civil service workers, it's probably clear as water that the existential consequences of such things weren't considered when taking that decision. One of the most bizarre experiences in these times happened in March 27th, listening to the song "Murder Most Foul" by Bob Dylan.

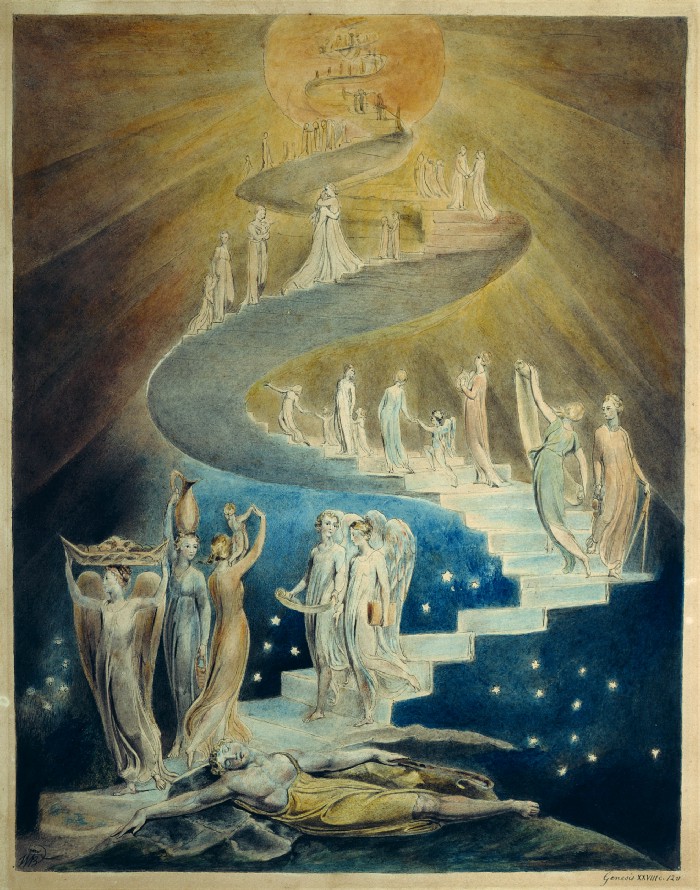

The longest song in all of the musician's career was reviving the American historical context that culminated in president Kennedy's death, one of the most crucial events in American 20th century history. But the song isn't simply a homage, or driven by nostalgia. As I said, it tries to revive the historical context. It's got a religious aura, like a Renewal Myth which tried to bring the spirit of an era that was about to end, announcing the End of the World, in religious terms¹. Although it starts with the End of the World, it regresses, going to the Beatles, Thelonious MOnk, Nat King Cole, then even back to Shakespeare nearly the end and so many other figures in between.

Although it's a very interesting song, it certainly wasn't the expected for a musician who didn't release any original music in 8 years. Even weirder was the fact that this song was the first Dylan song to top any Billboard chart. I mean, the guy couldn't do it even in the apex of his popularity, but he somehow convinced ten thousand people to buy a 17-minute long single with no commercial appeal? Now that's a feat.

This would already have been a present to the man's fans, who were anxious and hungery for new material — I appreciate what he did with Shadows in the Night, Fallen Angels and Triplicate (which I even reviewed in AOTY), but new material was unexpected outside bootlegs —, but in less than a month another single would come out. "I Contain Multitudes" was a very less distinct song, sonically speaking, but it had a little edge that the previous single simply didn't deliver. We all like an edgy Dylan, and lines such as "I'll sell you down the river, I'll put a price on your head/ What more can I tell you? I sleep with life and death in the same bed" satisfy that category, even though its overall tone is melancholic.

Again in less than a month, in May 8th we got a third single. "False Prophet", my favorite of the three, came out, proving Dylan as himself says in the lyrics, is "An enemy of strife/ I'm the enemy of an unlived, meaningless life". Even when 79 years old, the guy was still delivering, staying still rotting away isn't an option.

But even more important than that, in the same day "False Prophet" was released, we also got an announcement. In July 19th, we would get a new album called Rough and Rowdy Ways. I honestly didn't think this would happen again. For me, Tempest was the end of original songs for Dylan. In 2012, a journalist from Rolling Stone magazine asked him if the name of the album was a reference to Shakespeare's (one of Dylan's biggest influences) last piece. Dylan at the time didn't give too much attention, but until May 8th, 2020, we didn't have any evidence that Tempest would NOT be the singer-songwriter's last album of originals. Even I believed that, but happily this is not what happened. Ending his career with such a bitter album like Tempest wouldn't be the best way to do so. Tempest had nothing nostalgical about it, nothing redeptive, nothing. It was an album about betrayal, bitterness, violence and emptiness, themes that probably contributed to its quality, considering it's probably his best album since 1997's Time out of Mind.

I tried to avoid any experience with the album until its official release. If I wanted to, I'd easily find it online yesterday or the day before, but it didn't feel right. Not because I think piracy — tool that permitted me to develop my musical and aesthetic taste — should be fought against, but it just felt wrong. It coincided with a few other things that happened in my life, and June 19th ended up special one way or another.

And here we are. Listening to Rough and Rowdy Ways for the second time. The first one was about 12:10 am. The second one is happening 3:40 pm.

"I Contain Multitudes" opens the album. It's hard for me not to compare it to Tempest, since this was his last "real" album, and I find almost opposite characteristics than those of "Duquesne Whistle". Tempest's opening was uptempo, danceable, while at the same time showing a darker side when you watched the official video. But "I Contain Multitudes" is different while showing Dylan with some humor mixed to the melancholic lyrics. Not only the edgy lines I mentioned before, but others such as "I'll keep the path open, the path of my mind/ I'll see to it that there's no love left behind", which would be excessively serious in the same spirit as "Duquesne Whistle"'s video, being preceded by others almost humoristic: "Get lost, madam, get up off my knee/ Keep your mouth away from me". Namedropping the Rolling Stones aside Anne Frank and Indiana Jones also shows that we don't have a single point of view to follow the entire song. In a recent NY Times interview, Dylan said "The song is like a painting, you can’t see it all at once if you’re standing too close. The individual pieces are just part of a whole."

Extending this mentality to the entire album, we can put the following song, the also known "False Prophet", in some sort of context. Dylan is walking through places "where only the lonely can go", but with an essentially triunphant tone, best exemplified in the sixth verse: "I searched the world over/ For the Holy Grail/ I sing songs of love/ And I sing songs of betrayal/ Don't care what I drink/ I don't care what I eat/ I climb the mountains of swords on my bare feet". Dylan is a veteran, and this is the development of an idea already present in the song, such as in the fourth verse, where he talks about his own generation slowly going away: "I'm first among equals/ Second to none/ The last of the best/ You can bury the rest/ Bury 'em naked with their silver and their gold/ Put 'em six feet under and I pray for their souls".

This verse is specially peculiar when you consider that Dylan was never the center of attention, that carried gold and silver, and always kept behind other people's success, writing songs that would be hits in the voices of others, from Peter, Paul and Mary to Adele.

By this point, I've heard the album for the second time and I'm in the third one. It's 7:20 pm, June 19th.

"My Own version of You" is a weird song, in the best of senses. As Frankenstein, Dylan is building a creature, but not a monster. He searches for the most virtuous and uses their virtues to "bring someone to life, someone for real". Al Pacino, Marlon Brando, Julius Cesar, Leon Russel (pop composer behind hits throughout all his life until his death in 2016), Liberace, St. John the Apostle, Saint Peter are some of the figures Dylan keeps as ideals for that who will be brought to life. At the end of the day, it's Dylan looking for the absolute moral peak of the individual, which turns this song weirdly about... God. This song was different for me each time it was heard, and I'm sure more will emerge out of it as time passes.

Another interesting thing is Dylan's attack to Freud, putting him aside Marx as "some of the best known enemies of mankind". It's not the first time Dylan mentions Marx under bad lights, but Freud debuts in this department in the last verse of the song, which grows tremendously comparative to the rest of the music because of its longer length.

Up next, "I've Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You" comes, with a spirit similar to that of Time out of Mind's "Make You Feel My Love", which is a song that although written with some amorous suggestion can be interpreted under religious lenses. The first time it was brought to me that way was with Bishop Barron, who, in an episode of the Word on Fire Show, talks about the figure of one of his heroes, Bob Dylan. The difference is that, opposite to more than 20 years old song, "I've Made Up My Mind" has a direct religious reference: "If I had the wings of a snow white dove/ I'd preach the gospel, the gospel of love/ A love so real, a love so true/ I've made up my mind to give myself to you". But regardless of this religious presence, Dylan still keeps things foggy in the end: "I've travelled from the mountains to the sea/ I hope that the gods go easy with me/ I knew you'd say yes, I'm saying it too/ I've made up my mind to give myself to you".

"Black Rider" is the "rawest" song of the album, with minimalistic instrumentation. When I heard it for the first time, about 20 hours ago, I had chills down my spine. It references the Great American Songbook (the collection of American songs Dylan spent 2015 to 2017 interpreting), biblical ideas and it ends in a very peculiar note, almost combative to the tough, tricky yet worthy of empathy shady figure the song is written for.

"Black rider, black rider, all dressed in black/ I'm walking away, you try to make me look back/ My heart is at rest, I'd like to keep it that way/ I don't want to fight, at least not today" is the first biblical reference (or, at the very least, archetypical, since it's present in the myth of Orpheus for example) remembering Lot's wife, who became a pillar of salt when she looked back to the destruction of Sodom. Not only that, but "You fell into the fire and you're eating the flame/ Better seal up your lips if you wanna stay in the game" also references another biblical story, this time from the Book of Isaiah (which had already been inspiration for one of Dylan's best known songs, "All Along the Watchtower") where the prophet has his lips burned with ember as a cleanse of his sins.

Then "Goodbye Jimmy Reed" begins, one of the most peculiar songs of the album. It starts with a reference, shared by Captain Beefheart in the song "Moonlight on Vermont", to a traditional song called "Old Time Religion", which's got a version even by Pete Seeger. Given the previous song, it's no surprise to find appreciation to traditional religion.

I'm in the third and a half (it's not the fourth but we're almost there) play of the album, and it's 10:44pm.

"Mother of Muses" is, as the name suggests, a homage to Dylan's inspirational muse. The problem is that this muse is a series of events, people and things. In a verse, Dylan mentions the heroes of the 50s and 60s and those who paved the way for the cultural events that followed. "Sing of Sherman, Montgomery and Scott/ And of Zhukov, and Patton, and the battles they fought/ Who cleared the path for Presley to sing/ Who carved the path for Martin Luther King". Obviously, Dylan is talking about the Alliance in World War II. Next, he mentiones the most distinct among Homeric muses, Calliope, and calls for the mother of muses: "Mother of Muses, wherever you are/ I've already outlived my life by far". This feels like a callback to "False Prophet" and its lines about him being "the last of the best". Cohen, Little Richard and obviously Elvis and so many others are already gone. One by one his heroes and his own generation go.

It's known that Dylan has deep Roman influences, and in "Crossing the Rubicon" he adds one more reference to that list. The Rubicon river was the place through which Julius Caesar crossed, beginning the Roman civil war, which ended with Caesar turning into the emperor. It's also known that Dylan has always had this fascination for Roman history, and he has already said that, had things gone a little different, he would end up teaching Roman history. The references in the 2000s albums are known and frequently considered "thefts". 2006's Modern Times is full of lines from Ovid, the exile poet, and Virgil. My favorite reference until today is from Love and Theft, the 2001 album, in the song "Lonesome Day Blues: "I'm gonna spare the defeated, boys, I'm going to tame the crowd/ I am going to teach peace to the conquered, I'm gonna tame the proud", with its clear inspiration in the Aenid: "but yours will be the rulership of nations/ remember Roman, these will be your arts/ to teach the ways of peace to those you conquer/ to spare the defeated peoples, tame the proud".

Not only that, the Roman civil war has another appearance in Dylan's career, in the same album as "Lonesome Day Blues". "Bye and Bye" tells us: "Papa gone mad, mama she's feeling sad/ Well, I'm gonna baptize you on fire so you can sin no more/ I'm gonna establish my rule through civil war", with variations to "Papa gone mad, mama she's feeling sad/ I'll establish my rule through civil war/ Bring it on up the ocean's floor/ I'll take you higher just so you can see the fire", both of which have again the idea of purification through fire, like "Black Rider" and the Book of Isaiah.

Then "Crossing the Rubicon" revives the spirit of war that unites, or something in these lines. It's revived the idea of the End of the World and Renewal² in religious terms. War as in that which will bring order when it's done. The end as in that which will open the possibility of a new beginning. THe song is essentially the journey of beginning the process of change, of separating the tragic past of the hopeful, promising future, even if you need to dirty your own hands in the process. As Dylan himself says, "Well, you defiled the most lovely flowers/ In all her womanhood/ Others can be tolerant/ Others can be good/ I'll cut you up with a crooked knife/ Lord, and I'll miss you when you're gone/ I stood between Heaven and Earth/ And I crossed the Rubicon".

It's 11:43pm and I won't be able to publish this in the same day the album was out.

"Key West (Philosopher Pirate)" is the reiteration of a common theme in Dylan's career, represented by the likes of "Visions of Johanna" and "Highlands", and the journeys of "Isis", which take a new form. It starts wih one of the pillars of Dylan's career: American history. The first lines are about William McKinley, American presiden who was shot in war and succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt.

In itself, the song is a journey in search of some uncomprehensible ideal, much like the previously mentioned songs, and this uncomprehension is explicitly shown in contradictions: "Key West is the place to be/ If you're looking for immorality"*, "Key West is the gateway key/ To innocence and purity". The presence of some hallucinogenic spirit ("China blossoms of a toxic plant/ They can make you dizzy, I'd like to help you but I can't/ (...) Well the fish tail onds and the orchid trees/ They can give you that bleeding heart disease") also points to something in that direction. Also, the fact that Dylan mentions these hallucinogenic effects also bridges two generations he had seen closely in the past: the beatniks mentioned in the song and the hippies. Not that it's a reference to the guy but one of the figures that also has seen this transition was Ken Kesey, American author profoundly associated to psychedelia and who was known for using hallucinogenic drugs.

Dylan also talks about his relation with Judaism (a brilliant interpretation which, to be fair, I got from Genius): "Twelve years old, they put me on a suit/ Forced me to marry a prostitute/ There were gold fringes on her wedding dress/ That's my story, but not where it ends/ She's still cute and we're still friends". In this segment, Dylan references his bar mitzvah, that happened when he was 12, and compares himself to Hosea, told by God to marry a prostitute, and in the case of this song, the prostitute is the Torah, with "gold fringes" in a "wedding dress" white. Although Dylan rejected Judaism and chose to follow Christianity, the whore "is still cute, and we're still friends".

It's 12:12am of the 20th, and I just noticed Judaism was represented by a whore.

Finally we get to the end of the album, with the first song to be released. "Murder Most Foul" is a mark, and not only for the commercial reasons previously mentioned. Out of all the songs Dylan recorded that had over ten minutes, this is the only one that doesn't have a mesmerizing repetition of the melody in an almost ritualistic way. As previously said, it begins in its climax, then goes to the description and contextualization of the event, going backwards in time. The melody, though, does the opposide: it starts shy, and then grows and grows. It's a very unique song in Dylan's catalogue. In 14 minutes, "Tempest", although fantastic, does not deliver a melody that builds up the narrative, for example.

The fact that the lyrics begin in its climax and the melody finishes with its climax gives a special feeling. It makes all the song, in its 17 minutes, be all the time in some sort of climax. The context is a climax in itself, all the artists Dylan mentions are the most important part of the story in a sense**.

Rough and Rowdy Ways is a Bob Dylan album that finally ends in a positive note, something uncommon. Tempest finished with mourning about John Lennon, Modern Times with "Ain't Talkin'", summarizing small (and great) tragedies, Love and Theft, an album mostly in good nature, with "Sugar Baby", a song that begins with Dylan lamenting the sunlight and ends in the indifference of "You went years without me/ Might as well keep going now". But now... now we finally end with an epic of all that made American culture so rich.

I needed more than 24 hours to write this. It's 12:32am and I feel I'll need a much longer time to digest what I heard. Rough and Rowdy Ways is a very, very good album.

* When I first heard the song, this is what i understood, but then I found out the lyrics were actually "Key West is the place to be/ If you're looking for immortality". This changes a lot this aspect that I mentioned in the song, and makes Dylan not deal with human contradictions, but with an abstract ideal of absolute greatness.

** It sounds convoluted, but my point was that at the same time Kennedy's death is the theme and the climax of narration, the artist leaders and their influences that Dylan mentions throughout the song also represent some sort of climax, which is alluded to by the instrumentation that gets bigger and bigger as he goes talking about these people.

¹ Eliade, Mircea. Myth and Reality, chapter 4

² Eliade, Mircea. Myth and Reality, chapter 3